By Stephanie Ortiz

We see legends as the finished product. There’s no beginning or end–they are: larger than life, unapproachable, so out of our league.

But the greatest, immortalized on a mural, are the ones like Wali “Wonder” Jones, who remind us where they come from and who they are. They empower us to be champions, too.

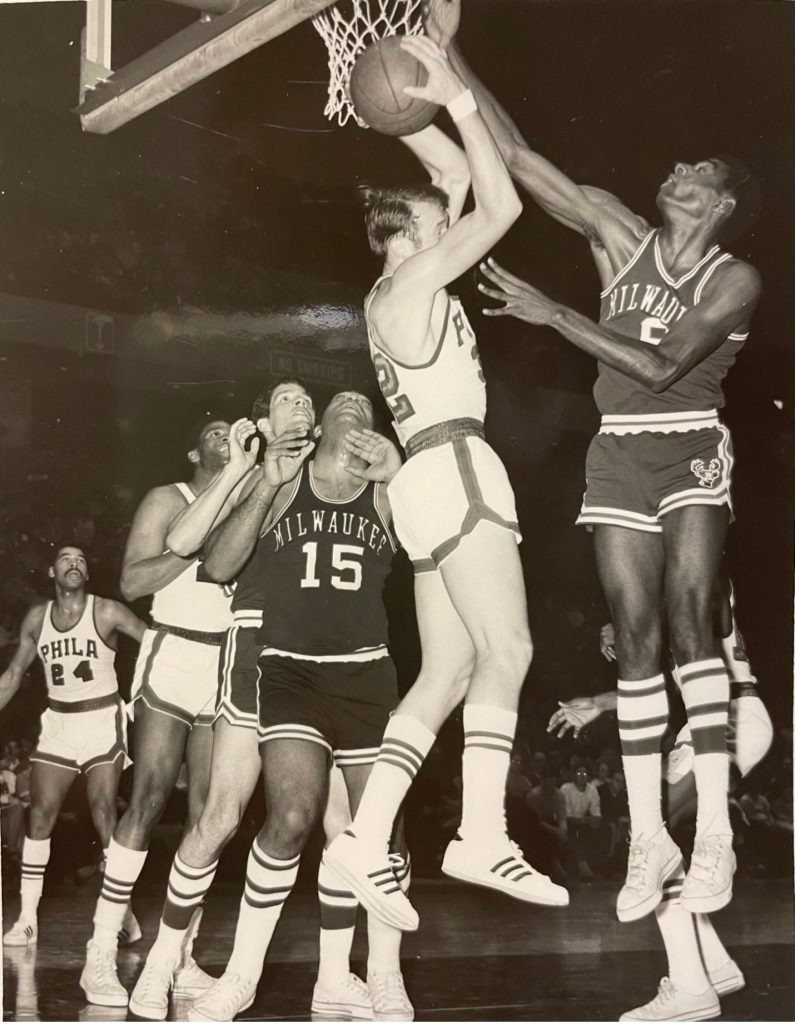

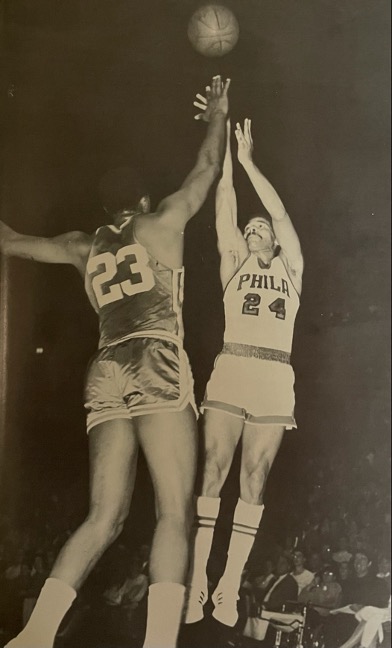

Even as Bill Cunningham’s daughter, I’ve dreamed about the tall tales and basketball legends that began when Dad as the Kangaroo Kid and Wali as Wali “Wonder” were 76ers teammates before my birth. I could only imagine the fun!

I should have known Wali forever, but I only met him this year. We’ve had many phone conversations and two interviews (plus one with Matt DeLucia from NBC) with his Dad, 106-year-old Ernest “Pop” Jones.

Pop Jones still lives in the heart of West Philly and has stood by his community as another living legend in the Jones family.

But the bigger picture came together in April when Wali said there’d be a mural this summer.

Talk about bringing together the past and the present.

Even a 76ers basketball legend has a starting point, so Wali begins with this mural where he celebrates his roots in Mantua, colloquially called “the bottom.”

Thanks to Mural Arts Philadelphia, a mural is born here so frequently that no other city, including Paris, can boast what we can: Philadelphia has more murals than any city worldwide.

And by July 21st, the mural’s creators, Gabe Tiberino and Taqiy Muhammed, gave life to the blank wall at the playground at 37th and Mt.Vernon Streets with the Wali “Wonder” mural.

Wali said this mural cost $30,000, and though he’d ideally see that money earmarked for We Embrace Fatherhood, who sponsored the mural and Wali’s ongoing Shoot For The Stars training program, Wali wants this to be about something bigger than him. So he instructed the lead artist, Gabe, to make this mural about the kids.

Wali’s widely known as a point guard, and Gordie Jones, who writes for the 76ers, claimed in his 2020 Forbes article, “Sixers’ Finest Fives: Wali Jones, QB of the ’66-67 Title Team, Has Spent His Life Doing Good” that as far as Sixers history goes, Wali makes his top five players.

Many people want Wali honored on that note, including Gordie, who incidentally is unrelated given the shared last name.

Gordie captured Wali better than a family member could when he said, “Ever the point guard, the 78-year-old Jones veered here and there during a 52-minute conversation, changing topics as he once switched hands on the dribble.”

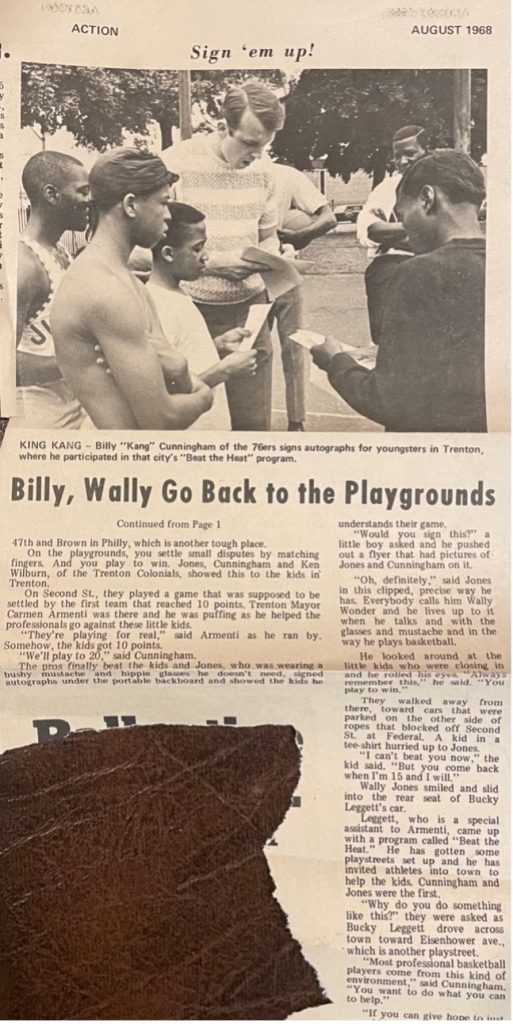

Still, Wali’s been doing basketball clinics for the kids since the 60s, and that part of his history he’s carried with him long since his professional playing days.

I’ve heard much about those basketball clinics from my Dad and Wali and how they’d go into local neighborhoods and work with the kids.

But having an opportunity to visit one of the Shoot For The Stars monthly basketball clinics a few weeks before the unveiling made me realize those clinics are ongoing, thanks to Wali’s continued work now with Coach Ken Hamilton.

Wali has a way of drawing you into his inner circle. He makes everyone feel so vital. And he’s no different at his clinic.

He had older kids be assistant coaches to the younger kids, and every adult there got to speak. Wali called me up there too.

No one said it had to be pretty, but when the kids clapped (maybe because my speech was so brief) and it was so hot (I mean inferno burning) so it might not have anything to do with what I said, or how I said it, but I felt so good about myself. I really can make a difference.

We’re all teammates–even me.

The day we saw the mural unveiled, the mural was already up. There was no unveiling, which came as a surprise to me. But having the mural as a backdrop to the festivities made the day all the more special.

The event opened as our hearts beat with the sound of the West Powelton Drum squad. Everyone played with as much pride as the little drummer boy in the middle of that group of elders.

Wali crawled to the podium with dramatic effect. He wanted to change the planned program, so his Dad could speak first. Pop Jones is 106, after all.

Pop Jones bypassed everyone in his wheelchair, which he needs to use for long outings now, wearing his City of Brotherly Love cap as he waited at the side of the podium for Wali to give him the microphone.

Pop Jones is the man who made Wali the legend he is today. And as Wali explained in another of our phone conversations, “My Dad and the other mentors that raised us, we’re passing the torch to others–to our younger generation to carry on.”

Wali wanted to ensure his Pop and his mother, Dorothea, got their rightful recognition for all they brought to that mural.

“My mother was very strict and did not play about being an academic.”

While she was an avid reader and taught her children to use their intellect, Pop Jones taught Wali his work ethic.

But because there was a program, and Wali had a community to thank when it was his turn again, he introduced his Dad, “Mr. Jones, if you’d like to say something, Pop. I heard you were on NBC 10 this morning, and they talked about “Enough is enough” (and “Silence the violence”).”

So Wali asked Pop Jones, “Pop do you have anything to say?”

“It’s nice to be here and see all these folks out. Years ago, we called this the bottom. I’m looking to see anyone I might know at that time.”

But these great men and women need money to grow their community with these grassroots endeavors. And there was Pop Jones with his audience.

“I have the biggest question; anybody got any money? Somebody’s got some money. I need some money today. That’ll get a chuckle out of you. I don’t need any money, but I’d wish you’d give me some.”

He joked about what mattered to him and spoke the way his generation only could when he said, “Wali, as my son, you did real nice, and your debts paid off with your credits.”

Representatives spoke from Mural Arts Philadelphia and the Mantua Civic Association, who one day hope to own the building behind the mural–upgrade their port-a-potties to real bathrooms. And Derek Pratt of We Embrace Fatherhood, the vision behind the mural, also spoke.

And then there was Coach Ken.

In High School, Coach Ken used to hang out at the Jones’ house, which could have been confused with the Haddington Recreation Center had it not been for the lack of a basketball court.

Coach Ken got up to the podium and tried to summarize his life with Wali in two minutes. “He’s a friend, and boy, is he good at that.”

And the friend of all friends, the brother of all brothers, the legend of all legends, Wali, got up to speak.

He said, “It’s a journey to make a difference…That mural is not for me; it’s for you.”

And “you” referred to all those mentioned thus far and so many people that Wali couldn’t possibly call out every name in the crowd of over two hundred assembled in the Mantua playground, though he tried.

He is a hero who believes in his community that believed in him. As he said in his speech that day, people were doing this when they were young.

It’s only fitting that Wali gives back to the community that backed him as he played basketball in the recreation centers as a kid and won the championship at Overbrook High School–Pop Jones is older than it, by the way.

And the Villanova basketball teammates–it was for them. Just as they came to his house for dinner, they came out to support Wali.

And the mural was for Wali’s family, still living in West Philly: his younger sisters Dorothea and Janette, whom he affectionately calls the guardians of the community, and Pop Jones. Even as retired school teachers, they haven’t stopped caring for everybody around them.

His younger brother Bill, one of the three Jones brothers who won local high school championships, came from Denver, where he’s Dean at George Washington High School.

Though unable to be there, Wali’s other departed siblings were there: Bob, nicknamed “Little Bobby,” who won his Overbrook HS championship in 1958 and played for six years with my Dad in the Baker League; John and Ernest, Jr., as Wali said was an intellectual like their mother.

And to the crowd, he said, “All of you are family; I am the object of you–this mural is you. I cannot emphasize enough how much family means.”

That family extends to Mike Sharp, albeit from northeast Philly, who continues to give back by supporting Shoot For The Stars.

I met Mike at the basketball clinic after Wali told the kids, “These clinics cost money, and here’s the man with the money.”

Other financial supporters make up that mural. Wali calls them the Legends of the City of Brotherly and Sisterly Love, including Sam Staten, Jr. (of Local Union 332), Gene Shaiken (of Almo Distribution), Mr. and Mrs. Pete Albert & Steam Fitters Local 420.

So when Wali pointed out Mike Sharp in the audience, he could have been talking about 50 others, saying, “Mike Sharp gave money, and he showed up. It was like 100 degrees that day–it’s important to be part of your community.”

And the mural was for the 76ers, teammates like Wilt, with family members representing him, and my Dad, who Wali mentioned multiple times in his speech.

As Wali said in a phone conversation, “You can’t forget your Dad. Your Dad and I are brothers.”

Wali wants everyone to know about our City of Brotherly and Sisterly Love. “As he said, It means so much to show how close we were as a group in Philadelphia.”

That group is still close. It’s just history repeating itself in new and miraculous ways.

We’re all teammates.

It was a tremendous feat for Wali to thank every person who meant something to him. He’s still upset about the handful of people he missed mentioning, like Mike Goings from the 76ers; he’s provided memorabilia and Wali’s star kids with tickets for eight years.

It’s a once-in-a-lifetime event when a picture brings together a community of legends.

When West Philly honors Wali, Wali honors all who have helped him.

Pop Jones didn’t need to say he was proud of Wali. You just had to look at him to know how proud he was of his son.

The tears welled in his eyes when he sat under the tent after his speech, taking in all he could.

When the podium, tents, chairs, cameras, and all traces of the day are gone, the kids will play on their basketball court with the mural of Wali to remind them. They can imagine growing up like Wali, as Magic Johnson once did as a kid.

That mural raises the consciousness of the community of Mantua- the bottom, as those who are West Philly refer to it.

And though I can’t pronounce Mantua like a West Philadelphian, I know I’m part of the community no matter how I say it.

And now, three figures of Wali from different life stages, the kids and the sun, are part of the backdrop of the playground in Mantua. It’s Wali’s gift to remind Mantua the sun shines for them.

It’s a Wali “Wonder” Full life every day that it does.

Bottoms up, Mantua!

May that mural and the legends of the city of brotherly love behind it bring you and all the generations ahead hope, love, and prosperity- that sun lights the way.

It’s there to shine through the dark times, and it’s up to us to light our torches by it and raise everyone at “the bottom” to new heights!

“In closing, I have to say this,” Wali said. “We’re family. We’re humans on the journey to make a difference. If not you, who? If not now, when? If not here, where?”

Edited & Published by Carmen Greger