The following has graciously been provided by the sons of Edward L. Fenimore.

Edward L. Fenimore, Innovative Bubble Gum Manufacturer, 96

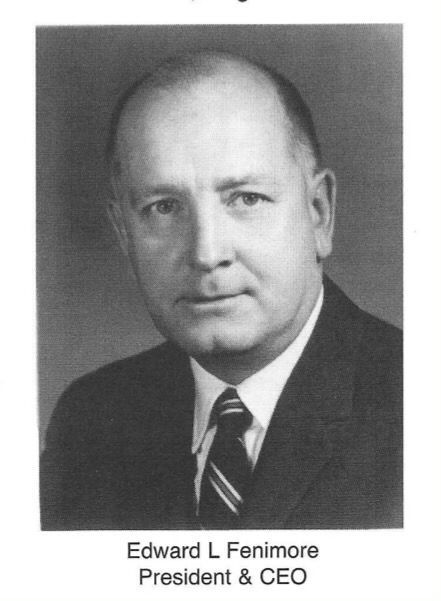

Philadelphia native Edward L. Fenimore passed away peacefully at Brandywine at Haverford Estates on October 30th, 2018, surrounded by family members. In over 50 years of manufacturing bubble gum and other confectionary products, he never lost sight of being, as he liked to say, “in the children’s entertainment business.” A World War II veteran, he improved the flavor and chewability of bubble gum by adapting products and processes originally developed for wartime use. Many local residents remember how, for many decades, his Philadelphia Chewing Gum factory at Eagle and Lawrence roads in Havertown perfumed the surrounding air with fragrances of tutti-frutti and powdered sugar. Born in 1922 in Philadelphia, Fenimore lived in Haddonfield, NJ until he was six, when his parents moved to Drexel Hill. He attended Beverly Hills Middle School and graduated from Upper Darby High in 1939. He spent summer vacations working for the Bowman Gum Company in Philadelphia, where his father, University of Pennsylvania professor of chemical engineering Edward P. Fenimore, was a consulting chemist. The younger Fenimore learned promotion and merchandising from world-trotting Warren Bowman himself, a colorful native of Lancaster known in the 1930s and 40s as the “Bubble Gum King.”

Fenimore was descended from a long line of engineers, manufacturers, and inventors. In 1879 his great-uncle Thomas Walker’s machine shop won a silver medal from the Franklin Institute for inventing the “Lightning Mill” – prophetically, an improved device for grinding sugar. Fenimore’s father spent much of his spare time in his Belfield Avenue basement, tinkering with early high-fidelity music systems and other entrepreneurial projects.

Graduating from Penn at age 20 with a degree in chemical engineering, Fenimore went to work for Standard Oil, in Elizabeth, NJ, on a defense-related WWII project. Since the Japanese Empire had cut off natural rubber supplies from Southeast Asia, the US government was crash-funding research into synthetic rubber. When one of the pilot plants he helped to design and manage finally proved successful, and Allied vehicles began to roll on butyl rubber tires and tank treads, Fenimore decided, against his father’s wishes, to enlist as a lieutenant in the US Navy. Aboard the minesweeper USS Embattle, he took part in operations in the Caribbean, the South Pacific, and Japanese and Chinese coastal waters. His ship was eventually picked to participate in the invasion of the Japanese Islands. But, as they were steaming towards the target, news came over the radio that a weapon of a totally new and vastly destructive kind had been used on two Japanese cities, and Emperor Hirohito had surrendered.

While in the navy, Fenimore had pursued advanced studies at Harvard, NYU, Princeton, and in Hawaii. Thanks to courses in theoretical physics, he was one of the few on board his ship to know what kind of bomb had been dropped. In fact, not long before Fenimore enlisted, family friend Harold Urey, the Nobel prize-winning discoverer of heavy water, had offered him a job on the Manhattan Project. Fenimore, however, turned him down. This he later credited to a pronounced distaste for pure science, and a genetic preference for applied technology and private enterprise.

After V-J Day, his ship’s mission changed from invasion to occupation, and Fenimore began training Japanese minesweepers to clear their own harbors. He had the opportunity to visit Hiroshima, a month after it had been leveled by the first A-bomb. He told stories of survivors huddled in collapsed buildings and the total devastation at ground zero. One day, a Japanese officer he had befriended took him to a hidden cove along the coast south of Osaka, where he saw thousands of abandoned kamikaze motorboats, previously under construction for a last-ditch counterattack on the expected Allied invading force.

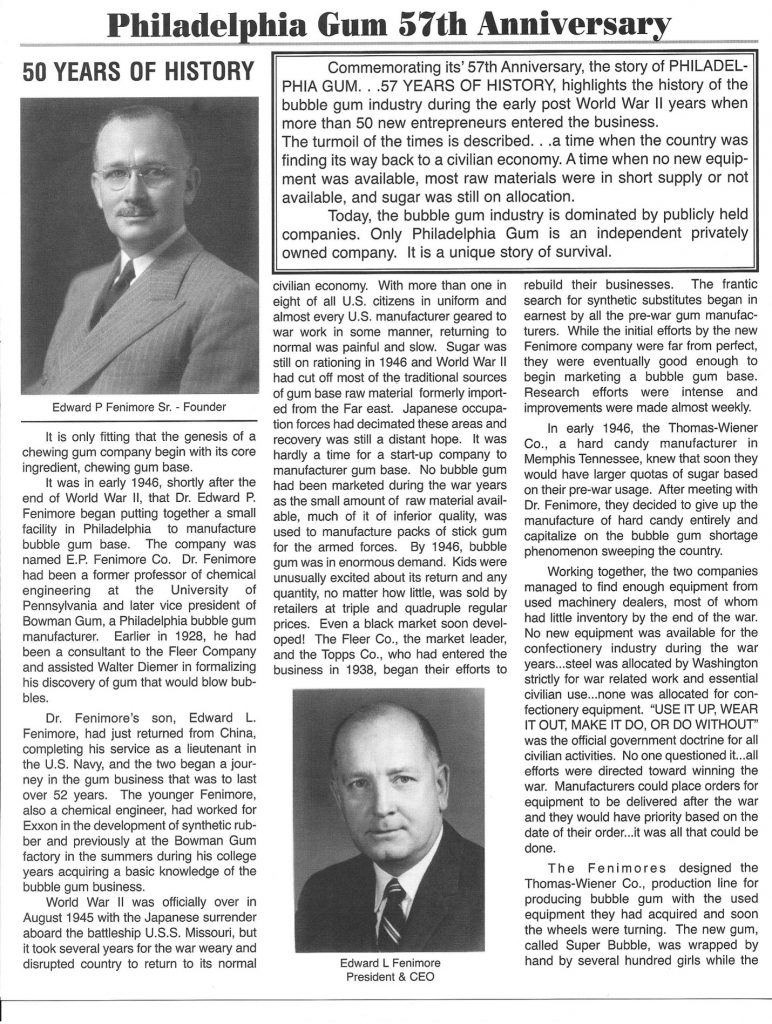

Following the war, Fenimore returned to Philadelphia and with his father went full-steam into the bubble-gum business. They bought a used gunpowder mixing kettle from a munitions factory, setting it up in a garage on Rittenhouse Street in Germantown. They began experimenting with gum base, which when combined with sugar, color and flavor is the main ingredient in all gum. The father-son engineering team blended various waxes and resins – some of them derived from synthetic rubber technology – until they hit on a formula yielding increased elasticity and chewability at all temperatures, plus better retention of sweetness and flavor. The E. P. Fenimore Company made its mark selling this improved gum base to numerous manufacturers throughout the US. As soon as sugar rationing eased and peacetime supplies became more plentiful, they turned to manufacturing and selling their own bubble gum, at first employing family members to cut, wrap, and pack the product.

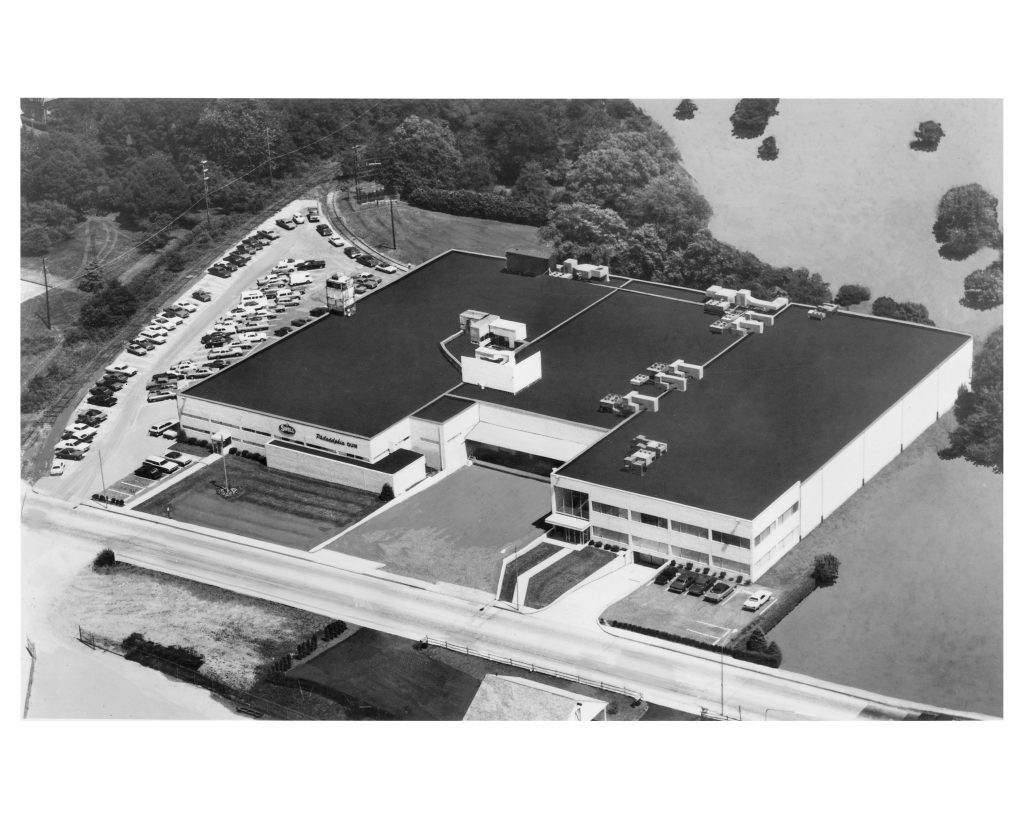

The postwar economy was booming. In 1948 they moved operations to a 10,000 sq. ft. building in Havertown and changed their name to the Philadelphia Chewing Gum Corporation. They would eventually employ an average of several hundred local residents, some of whose children also worked for “Philly Gum” over summer vacations.

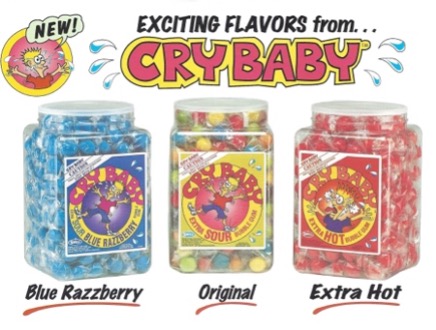

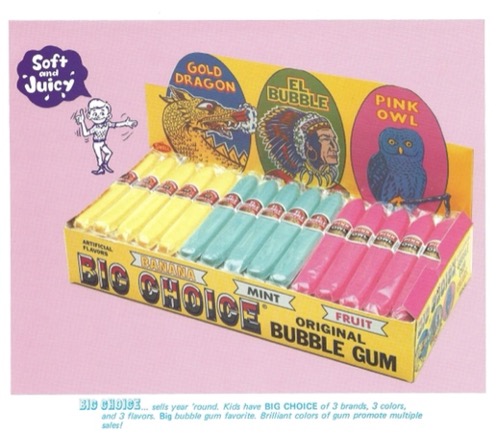

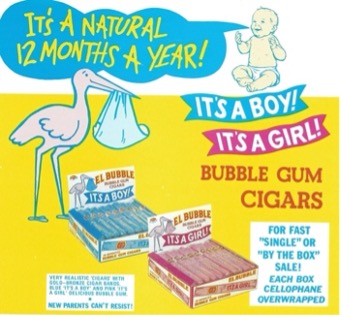

Their flagship brand was trademarked “Swell,” and the line would later expand to include numerous novelty products, including twist-wrapped Swell, bubble gum cigarettes, and the iconic El Bubble pink, yellow, and green bubble gum cigars – the first five-cent piece of gum.

That same year, Fenimore married his next-door neighbor, Edith Warner Heston, an accomplished cellist and member of one of Philadelphia’s oldest families. She was directly descended from Col. Edward Warner Heston, who served on Washington’s staff during the Revolutionary War and later founded Hestonville, now part of West Philadelphia. The young couple lived in Ardmore until 1957, when they moved to Bryn Mawr and a larger home Fenimore personally designed to accommodate his growing family.

After his father died in 1955, the 33-year-old Fenimore became president of the company and had soon expanded the manufacturing plant to 200,000 sq. ft. By then he was selling gum and other candy products in all 50 states and over 30 countries around the world, as well as shipping gum base to many smaller manufacturers at home and abroad. For 10 years he served as chairman of the National Association of Chewing Gum Manufacturers, representing them at annual meetings of the affiliated worldwide organization. In 2003, when Philadelphia Chewing Gum sold to Concord Confections, a Canadian company, the association honored him as a “Dean of the Industry.”

It wasn’t all hard work, though. In the mid-1960s Fenimore was asked to be a contestant on the CBS panel show What’s My Line, and when panelist Arlene Francis quickly guessed his profession, he entertained the audience by demonstrating how to blow a bubble inside a bubble inside a bubble.

He traveled the world and made a lot of gum-chewing children happy, but the loves of Edward L. Fenimore’s life were always his family, his business, and his beloved “Pink House” at the south end of Ocean City, NJ. He is predeceased by his wife, Edith Heston Fenimore, and survived by his grateful children: David (Ashley), Richard (Libby), Carol, and Edward P., II (Susan), eight grandchildren, and one great-grandson.